150 years of Abanindranath Tagore

150 years of Abanindranath Tagore

150 years of Abanindranath Tagore

collection stories

|

ARTIST IN FOCUS 150 years of Abanindranath TagoreAt the turn of the twentieth century, Abanindranath Tagore asked himself if the emerging artists of modern India should continue to paint in the manner of their European colonizers; or was there a new path waiting to be forged? His answers led him to envision a pan-Asian cultural identity, spanning traditions from Persia to Japan, and culminating in a 'new “Indian” art'. Regarded as the founder of the Bengal School, Abanindranath left an unparalleled legacy both in terms of his own diverse body of work, and through his pupils, like Nandalal Bose, who shaped the contours of art across the subcontinent in the twentieth century. |

|

ROOTS: JORASANKO ‘As I stayed by myself, my eyes gradually learnt to see, my ears to listen...A friendship blossomed between that enormous Jorasanko house and me, as it revealed itself in new ways through its nooks and crannies...Even the bricks and wooden frames spoke to me, we knew each other so well. That is where it all began for me.’ Jorasankor Dhaare [Around Jorasanko] Abanindranath Tagore was born into one of the most illustrious families of Bengal. He spent his early days at Jorasanko (literally twin bridges) in north Calcutta, whose memories return frequently in his oeuvre. |

|

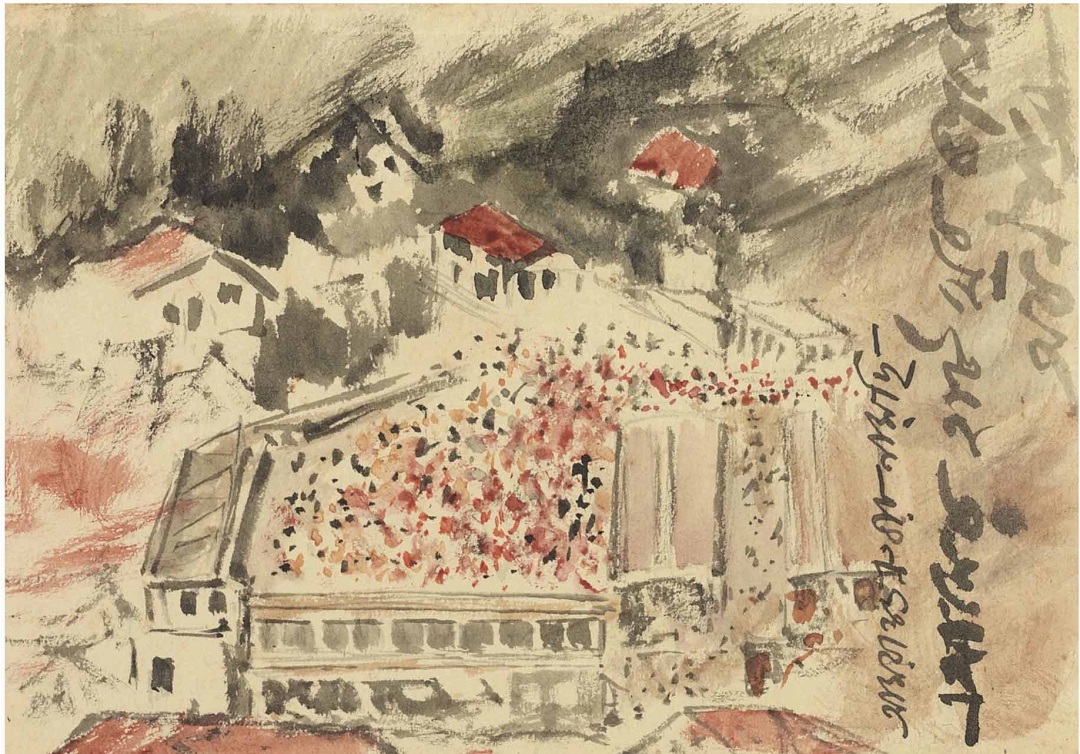

Abanindranath Tagore Jorasanko Bari (Jorasanko House) Collection: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi |

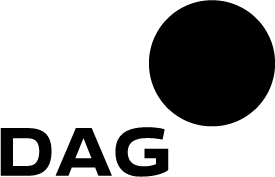

A ‘NEW INDIAN’ ART

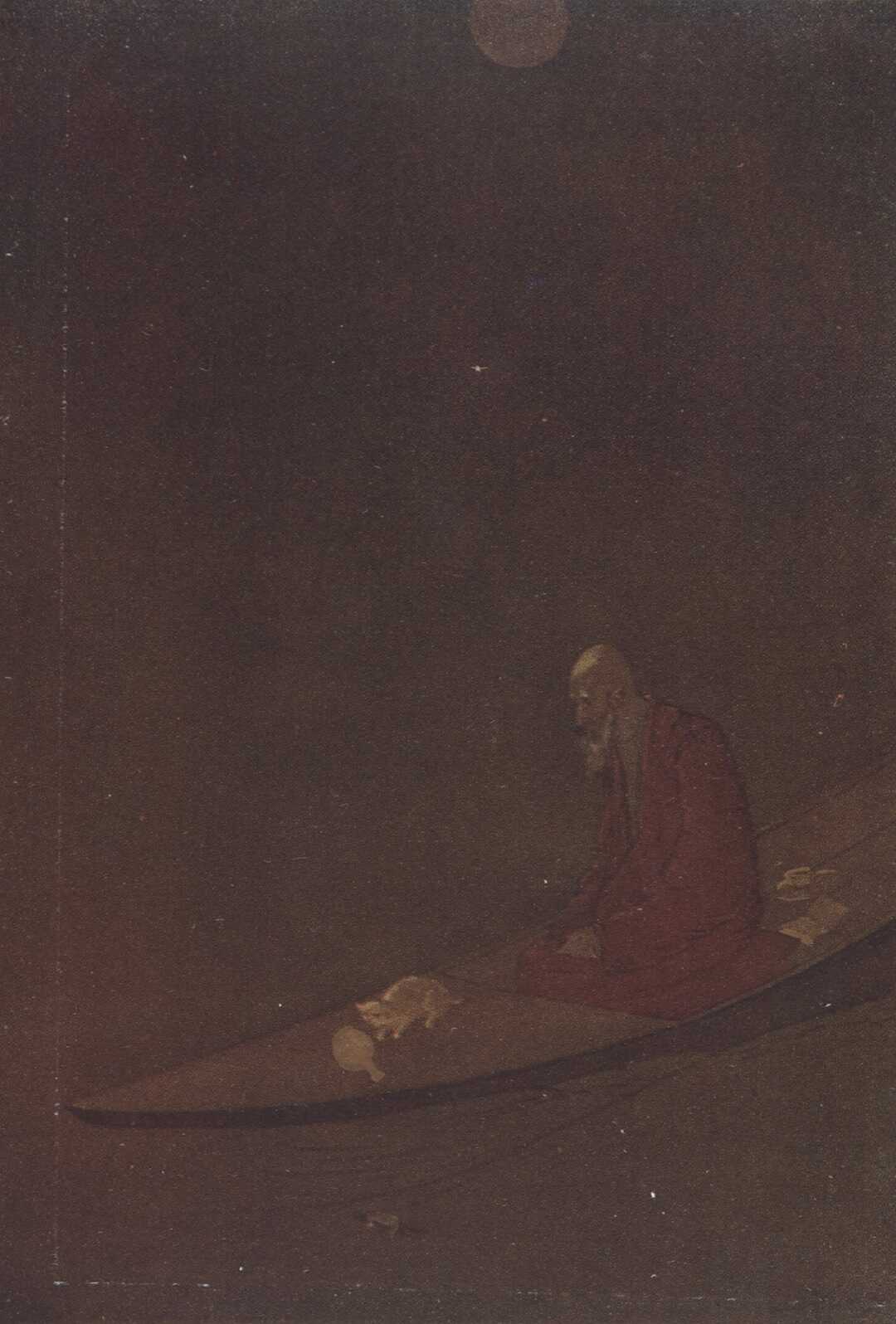

Abanindranath Tagore

The Passing of Shah Jahan

Abanindranath Tagore

Mother India (Bharat Mata)

In Abanindranath’s imagination, the new Indian art was meant to be more than a mere reflection of reality. The challenges involved envisioning an ideal that could be expressed through a syncretist coming together of visual traditions from across Asia.

Abanindranath Tagore

Untitled (Darjeeling Market)

Wash and ink on post card

1917

LOOKING EAST: NEW FRIENDSHIPS, NEW STYLESAbanindranath recalled his first encounter with Nihonga—art that emerged in Japan from the early twentieth century, in-keeping with traditional styles: ‘I remember the first time I saw [Yokoyama] Taikan (1868-1958) draw on silk with the faintest ink. I could barely see his lines...All he did was pick up a piece of charcoal to draw the basic form on silk. After that he dusted it carefully with a feather, before adding a touch of ink. That was it. Somewhat dismayed, I turned to Suren [Surendranath Tagore] (1872—1940), “Brother Suren, I can barely see what he’s painted.” Suren reassured me saying, “Just give it time, you will see it. It takes some getting used to.” He was quite right. It took me a few days but my eyes did get trained. I even started to appreciate them.’ |

|

CREATIVE COMMUNITIES The Bengal School, which marked a significant departure from the Western academic painting of the day, gained acceptance gradually. That story is one best told through the artistic alliances and societies that Abanindranath was a part of. Serious but often good-humoured discussions about the direction this new Indian art was to take are reflected in sketches, postcards as well as in articles in journals of the time, like Modern Review or Prabasi. |

|

Nandalal Bose Untitled (The Artists’ Studio, Jorasanko) Collection: DAG |

|

Nandalal Bose’s cartoon shows a colourful cast of characters from the Bichitra Studio seated in the south veranda of Jorasanko. Abanindranath, Samarendranath (1870 – 1951), and Gaganendranath (1867 – 1938) laze in the background, while the critic A.K.M. Coomaraswamy (1877 – 1947) debates some finer points with the artist himself. Abanindranath and Gaganendranath formed the Indian Society of Oriental Art in 1907, which gave a great impetus to their new experiments with Indian art. Alongside the male-dominated spaces of cultural encounter, his sisters, Sunayani and Binayani were coming into their own as exemplary artists. Skilled at music and embroidery, the sisters created their own visual language in painting. Explore |

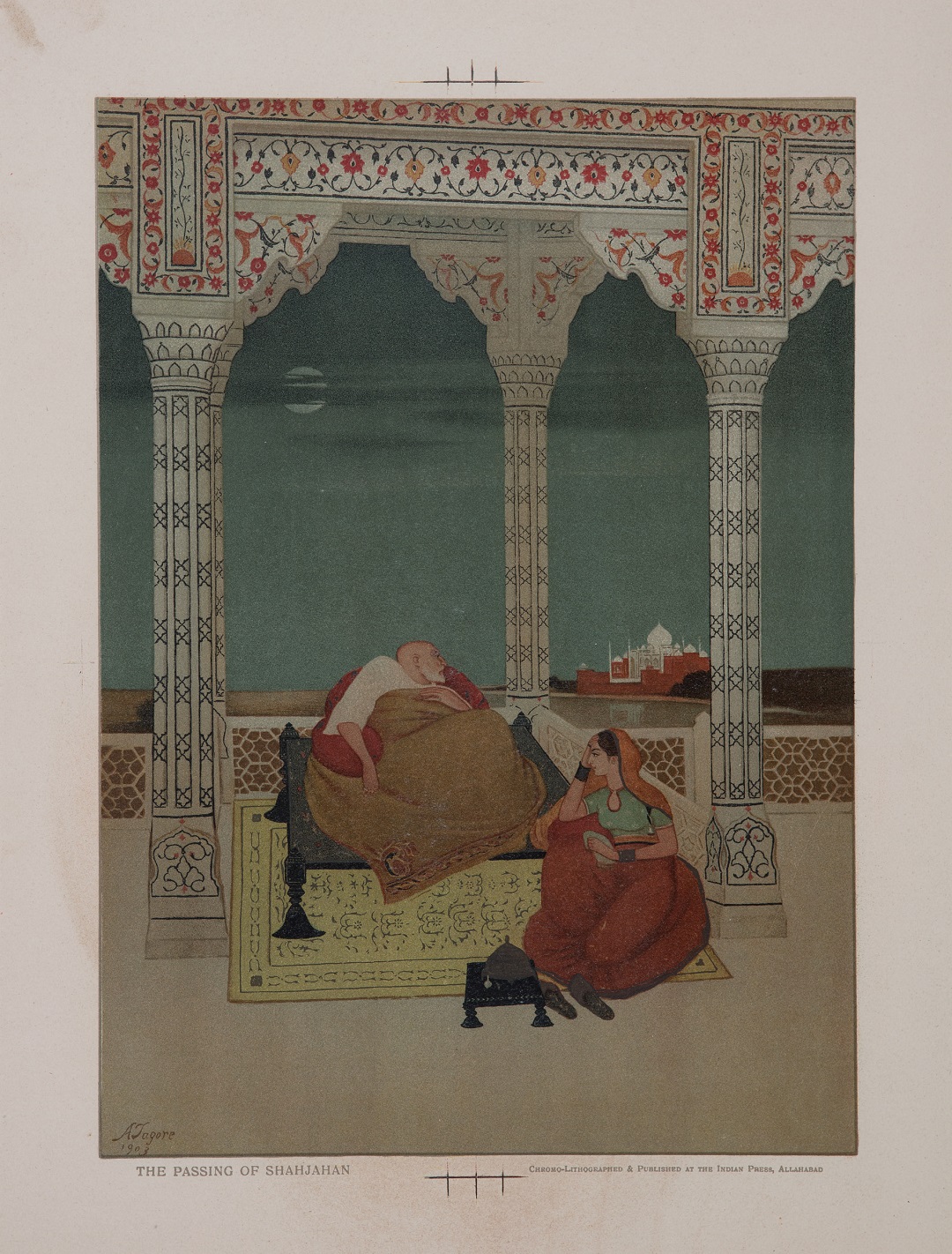

Abanindranath Tagore

Untitled (Shadow by River)

Gaganendranath Tagore

Untitled

Sunayani Devi

Untitled

Abanindranath Tagore

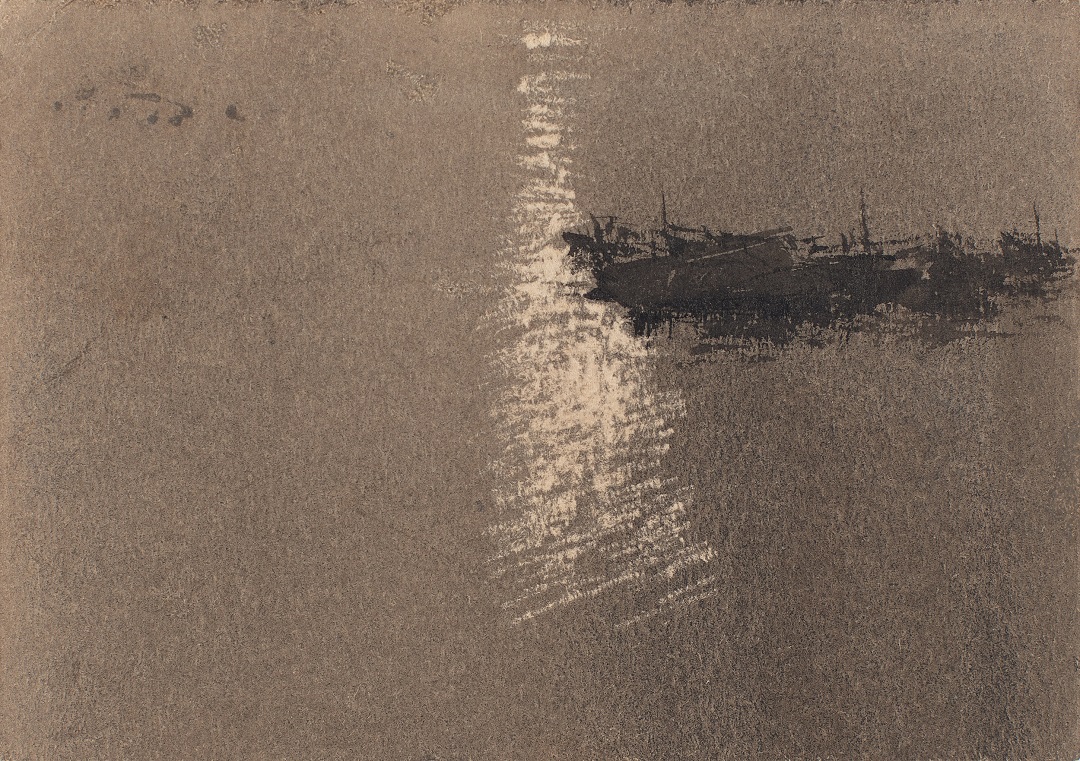

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Print on paper, hardcover four flap folder cover with a linen lining on the spine and glassine dust wrappers

THE STORYTELLERAbanindranath’s first forays into painting were in the form of illustrations for his uncle Rabindranath’s plays, as well as for his own story, Ksirer Putul (1896). He remained a story-teller throughout his life, re-imagining for his young audience age-old fables from different cultures, most notably the Arabian Nights, Krishna-lila, and Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat. In his final years, Abanindranath barely exhibited what he painted. It is said that he spent much of his time on the top floor of Jorasanko, carving wooden toys and spinning tales, perhaps to sustain his own fancy. |

|

The Legacy Apart from leaving behind a body of work that shaped the contours of modern Indian art, Abanindranath mentored artists like Nandalal Bose, Prosanto Roy, Asit Kumar Haldar and Mukul Dey, who carried forward his legacy and created their own. |

|

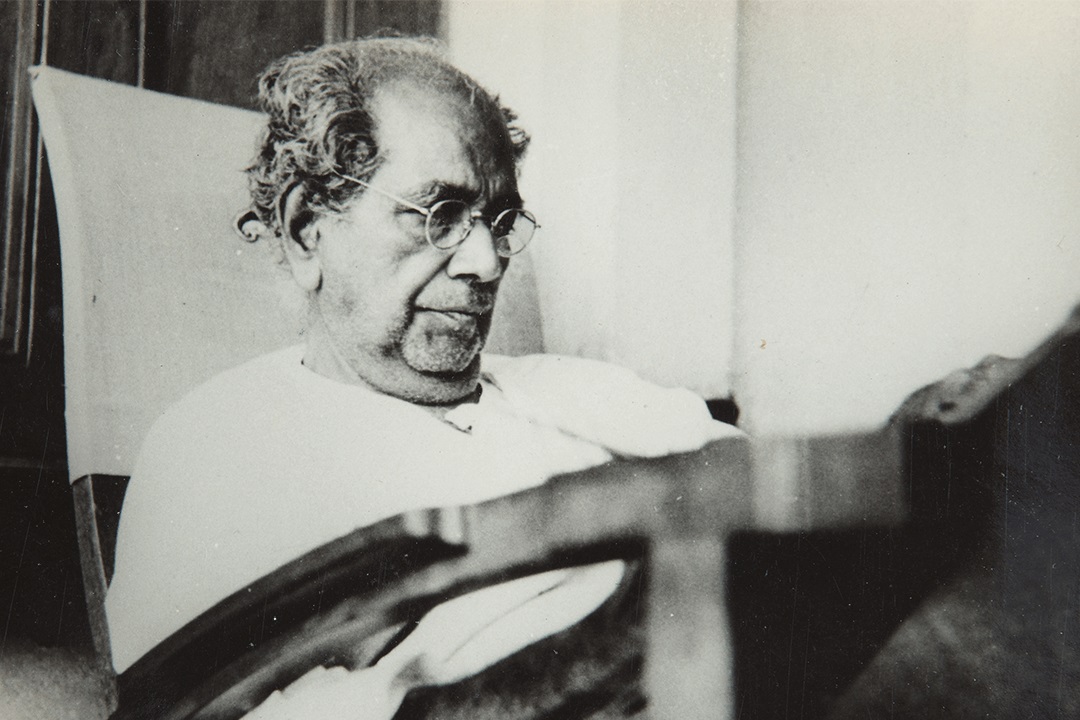

Abanindranath with his first batch of students at the Calcutta School of Art c. 1910 |

Nandalal Bose

Untitled

Asit Kumar Haldar

Untitled

Mukul Dey

Drawing the Net, Karatoa River, Pabna, East Bengal

Prosanto Roy

Untitled (Arabian Nights Series)